Learning from other organisations

Table of contents

Case study: Negotiating the challenges of doing co-research with people in the asylum system

Researchers for the SOLIDARITIES project (@Solidarities_) have considered the housing experiences of people in the asylum dispersal system in Yorkshire. The research has examined interactions between people in the asylum system and advocates around issues of housing access and support, with a focus on encounters with private housing providers, frontline service workers, and community members. Researchers asked who is rendered deserving, and how, in this context? A policy report about the research is available on the SOLIDARITIES website.

This research formed part of Migrants and solidarities: Negotiating deservingness in welfare micropublics (SOLIDARITIES). Funded by Nordforsk, it explores how solidarities are imagined and practised in negotiations of migrant deservingness. Researchers use an ethnographic approach with case study sites in the UK, Denmark, and Sweden.

The start of the fieldwork for the Yorkshire case study coincided with the beginning of the pandemic, which presented a challenge for the London-based researchers. As travel to Yorkshire and in-person fieldwork was not possible, six co-researchers were recruited with the help of the St Augustine’s Centre in Halifax, three men and three women, from five different countries in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. All the co-researchers had lived experience of the asylum system. Research participants were living in Doncaster and Halifax.

The research approach was collaborative and ethnographic, and included virtual and face-to-face participant observation, visual methods, interviews, and document analysis. The co-researchers were trained in these methods, and generated multimodal data in the form of text, photography, videos, and audios. Co-researchers were also trained in ethics, data analysis, and dissemination. Meetings and training sessions were held online once or twice each week.

As people within the asylum system are not normally allowed to access paid work, there was a challenge around adequately and appropriately recompensing the co-researchers for their time. They received compensation in the form of:

• gift cards

• mobile phones and data packages

• certificates of participation

• references.

The lead researchers also organised a webinar about access to and scholarships for higher education for refugees and people in the asylum system.

The lead researchers were conscious of issues around power dynamics and the need to avoid ‘transactional’ encounters. Priority was given to fostering a supportive and collaborative group dynamic through ice breaker exercises and follow-up one-to-one conversations between lead researchers and co-researchers. The co-research was developed iteratively through dialogue and listening. The research team was also aware of solidarities being enacted (and contested) in and through the research process, for example when one co-researcher learnt during the research process that their asylum application had been successful. A mutually supportive relationship between the lead and co-researchers has continued beyond the research process. Two co-researchers have subsequently gone on to work for a local third sector organisation supporting people in the asylum system.

In terms of ethics, there was sometimes a tension between institutional ethics versus on-the-ground embodied ethics. This manifested itself for example around questions over when face-to-face interviews were approved by the institutional ethics committee versus the situation on the ground in Halifax.

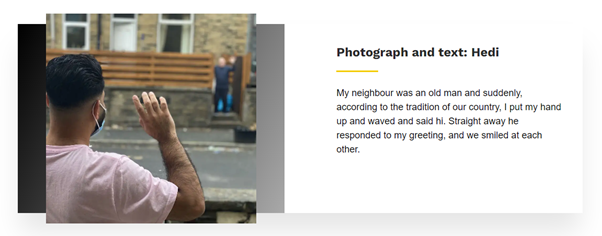

Positively, the co-researchers demonstrated feelings of ownership of the research, and expressed a desire to use the findings for positive change. Various activities resulted from this, including blog posts, talks, and public events. For example, they organised a stall about the project at an Open Day event at the St Augustine’s Centre in Halifax. In this powerful blog, co-researchers share their reflections through text and video on the financial support available to people seeking asylum. The dehumanising effects of the label ‘asylum seeker’ are eloquently described by two co-researchers in a blog entitled ‘My name is not “asylum seeker”.’ An online gallery was also generated collectively by the co-research process. This is an example of one of the images and accompanying text produced by a co-researcher:

Co-researcher Arsalan Ghasemi, who has since moved on to become activities coordinator for St Augustine’s Centre, reflects on what he gained from the research:

Improving my teamwork, learning to work with different people of different nationalities, improving my English because English is my fourth language, and also learning and experiencing new things and learning the basics of conducting research and interviews.

Arsalan considers the most challenging part of being a co-researcher ‘to be up to date and understanding all topics we had conversation about’.

Co-researcher Faith N shared her reflections on the research process:

I gained a lot of things. Number one, I gained friends. Another thing I gained is confidence, because when we’re doing the research, we had sessions where we had to talk and present our findings and discuss you know, so it just gives you a little bit of confidence. Another thing that I’ll say I have gained is a voice. Being part of a research, you know you are now able to express how you you’ve been feeling, you’re now able to say ‘no, this is not right’. So, I believe it was a platform that just gave me, and I believe my other fellow researchers, a voice to just speak out and speak on behalf of everyone else, the things that we face in our everyday life, which was really beautiful. What else did I gain from this research? The skills, when we were doing photography, and also we learnt about ethnography research, something that I wasn’t aware of, so it's just like an experience to me and new skills that I didn’t have and now have. And another thing is also, we got phones, we got data, but even after the end of this research we’re going to get references and I just feel it’s a CV booster. Now on my CV I can be able to say I did this project, this community project, and it’s an added advantage.

Faith’s advice to others: ‘If you find a project where you know your voice is gonna be amplified, you should do it! You should not fear. Fear is one thing that is holding many people back, especially if you don’t have your papers yet or your status yet. And just to be open, open to talk and open to hear other people’s stories and other people’s opinions, and to be accommodative. So that’s the advice that I would give them: just be strong.’

Sara Robinson, director of St Augustine’s Centre reflects on the benefits of the research project for the Centre:

We feel hugely privileged to being a partner in this really important piece of work for many reasons. It is bringing the voices and opinions of people with lived experience to the fore, and this is a key objective for us. We’ve learnt a lot through the project and the lead researchers were exemplary in the way that they facilitated the process, which resulted in a real sense of ownership from everybody involved. We’ve seen the impact it’s had on co-researchers, all of whom without exception have grown in their confidence and their abilities and sense of their human rights as a result.

Principal investigator Mette Louise Berg, Professor of migration and diaspora studies at @UCLSocRes reflects on the experience of co-research:

There were various constraints and challenges associated with doing co-research with people with current lived experience of the asylum system, especially during a pandemic. However, despite these, we were able to create a convivial and supportive space during the project. We sought to foster dialogue and mutual learning rather than an extractive ‘harvesting’ of data. The participatory co-research process produced rich and nuanced ethnographic material, which we then discussed collectively, prompting further reflections from the co-researchers.

The co-researchers were determined that the research should be meaningful and impactful, and enriched it in so many ways through their commitment, ideas, insights, astute analysis, and lived experience.

A note on ethnography:

Ethnography is a method that relies on co-presence and researcher participation. Ethnographers seek to understand the perspectives and view-points of research participants. A good guide to collaborative ethnographic research is Decolonizing Ethnography: Undocumented immigrants and new directions in social science by Carolina Alonso Bejarano et al. Carolina Alonso Bejarano talks about the book in an interview here.

The report from this project should be cited as follows:

Berg, M.L. and Dickson, E. with Abby, Faith, Hedi, Misbah Almisbahi, Nel, and Sanaa El-Khatib (2022) ‘Asylum housing in Yorkshire: a case study of two dispersal areas.’